London’s wooden block roads and their manufacturers, have been fairly well covered, by Ian Mansfield, in Ian Visits, [1], Mary Mills [2][3] and Carlton Reid in the fantastic ‘Roads Were Not Built For Cars’ [4] with a brilliant ‘Sherlock Holmes’ skit on road surfaces, Don Clow for the Greater London Industrial Archaeology Society [5] and in the fascinating End Grain [6], so this post has little to offer in terms of discovery, but it’s still a wonderous thing that maybe 100s of 1000s of wooden blocks, from Sweden and Canada and Australia, lurk beneath London’s tarmac, like with the granite setts that still exist in their millions across London.

There is a long history of the use of wood, mostly planks, for pathways in Britain, in London e.g. at Silvertown and Belmarsh, respectively c5000 and c6000 years ago, [7] and it’s probably that plank paths and roads have been used since then up to the modern day.

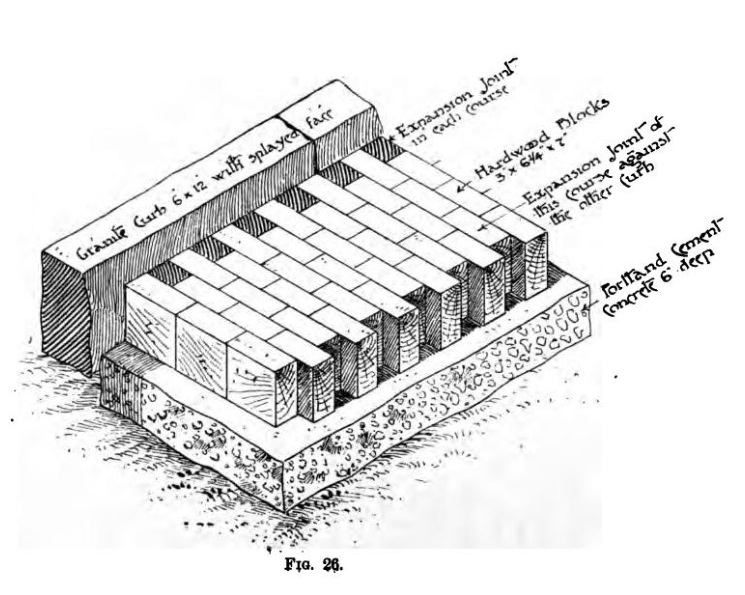

But in the 19thC it was realised that cutting wood on the end grain made strong weight resistant blocks, that were not just hard wearing but much quieter than granite setts, which while tougher also needed replacing after a few years. Through the 19thC there was a battle between macadam, granite, wooden sets then asphalt as to what surfaces worked best in cities for carts, carriages and horses, with wood block being popular at both the mid century and again at the end, and even into the 20thC. Building London won’t go into much detail on the history and simply again recommend the links above, though some of the factors are particularly fascinating: one of the downsides of the soft wooden blocks was they absorbed horse urine! [1] and when carts and carriages went over those sodden blocks the urine would squirt out at speed showering all in the vicinity! [4] A later change to Australian hardwoods and coal tar impregnated blocks was partly due to the need to have less urine squirting streets!

In 1884 it was stated at a discussion at the Institution of Civil Engineers on road surfacing, that

“Wood might answer for wide, well-ventilated thoroughfares, but to use it for narrow streets was anti-hygienic.

Wood absorbed the urine of horses and the diluted filth of the street; horse-dung clung to it, and in dry weather it gave rise to horse-dung dust. For traffic, wood was excellent for the first two or three years, but as soon as it became fibrous and worn, like an old tooth-brush, it would certainly produce poisonous emanations under a hot sun, and remain damp in winter. It lacked that first quality for an hygienic roadway, of impermeability and was far less durable than asphalt.” [8]

Different woods, hard and soft, and different grouts of asphalt and cement were also experimented with in terms of expansion and contraction and consequent surface evenness and smoothness for vehicles that used them , but also, somewhat surprisingly re anti-social behaviour of the time! In 1907, in the midst of a roller-skating craze, it was found that “… although the section of the roadway grouted with pitch is in very good order, it is distinctly more un-even than the cement-grouted section, on which the youngsters of the neighbourhood disport themselves on roller skates when they are able to avoid the attention of the police.” [9]

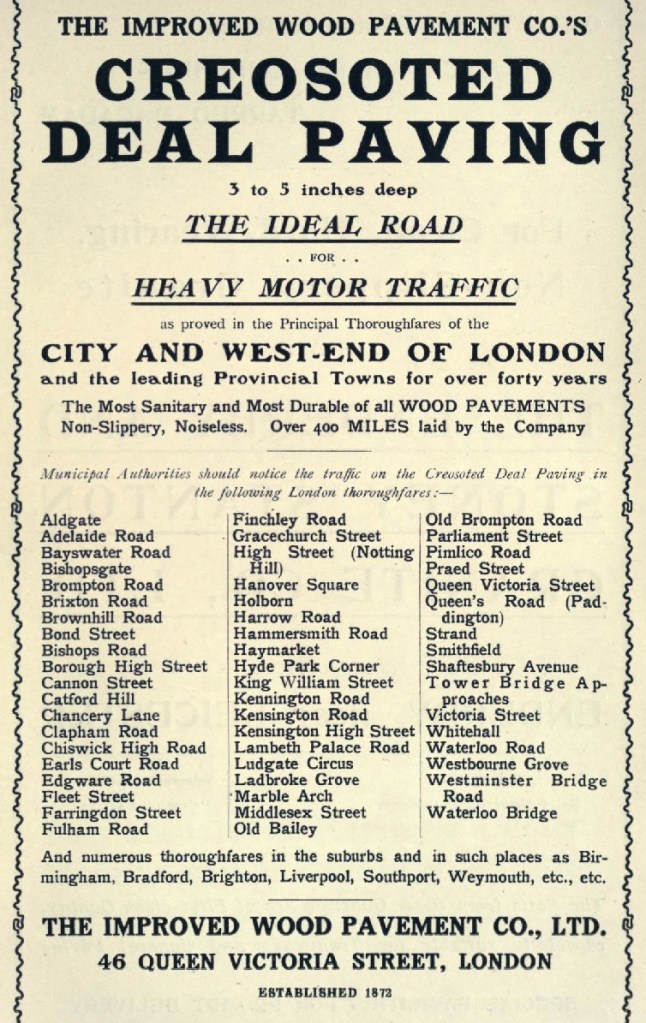

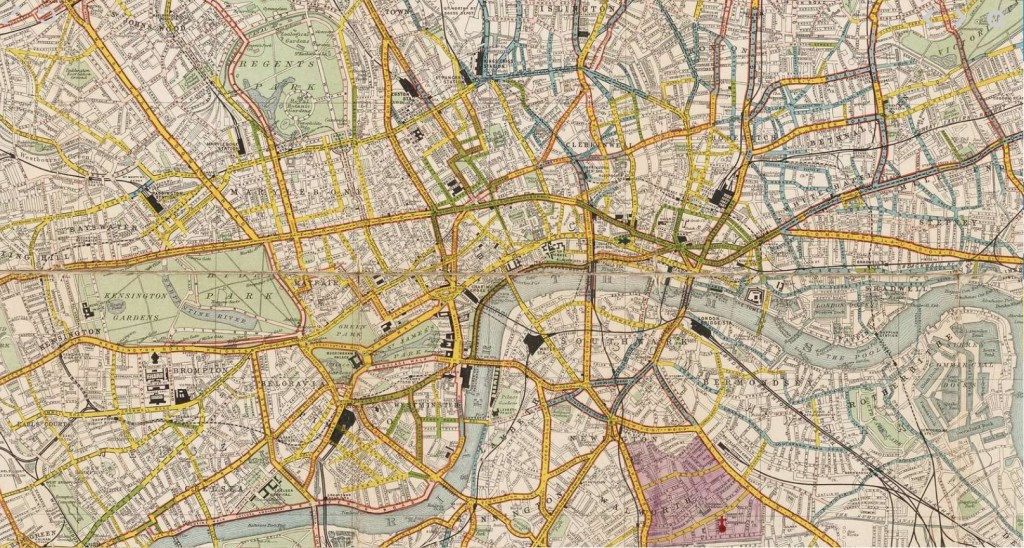

The use of wooden blocks became very widespread in London by the early 20thC, and End Grain notes that in 1912 “In 10 of the 28 London boroughs there was 121 miles of creosoted wood block … including 40 miles in the city of Westminster” and that “The quantity of timber used by Great Britain for paving in 1913 was estimated to be 60 million feet.” continuing “London’s most famous streets were still covered in wood blocks until the 1920s and a few into the 1930s. ‘Bartholomew’s Road Surface Map of London’ from 1922, shows most of London’s roads surfaced with wooden blocks. A copy is held by the National Library of Scotland. However, by 1925, wood paving was finished as a road material and was replaced with tarmacadam.” [6]

Mary Mills Greenwich and Woolwich at Work / London Borough of Greenwich

Bartholomew’s Road Surface Map of London and Neighbourhood 1928 shows most of central London streets, in yellow, surfaced with wooden blocks, compared with asphalt, green, and granite setts, blue.

Universiteitsbibliotheek Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam

in the wooden block road paving, London, c1925. (Seymour Lincoln/Getty Images)

What wood was used and where was it from.

Both soft and hardwoods were used. The former were cheap and easily available, Deal aka Pine, coming from the Baltic, often from Sweden, or Canada, but were too soft and absobant until it was learnt how to impregnate them with coal tar, in the late 19thC.

With the late 19thC revival in wooden paving Australian hardwoods also became much used, Jarrah wood, Eucalyptus marginata [10] and the Karri, Eucalyptus diversicolor, [11] both enormous trees in their native south-western Australia Jarrah Forest. [12]

Manufactured in London

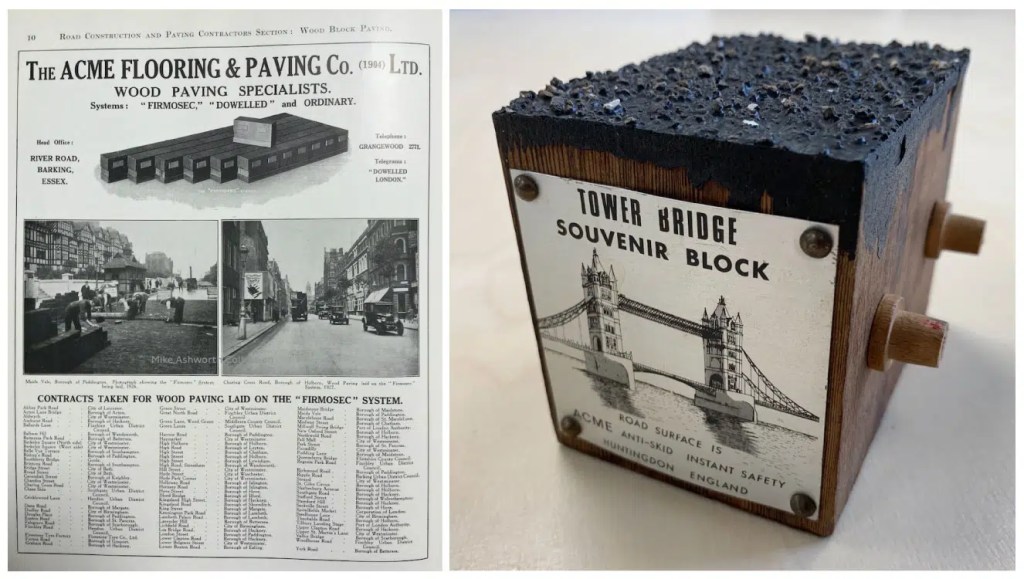

While the wood was mainly imported, the blocks themselves were made in London. Companies included the Wood Pavement Co. which morphed into the Improved Wood Pavement Company Limited, [2] the Asphaltic Wood Paving Company and the Acme Wood Paving Company. [13]

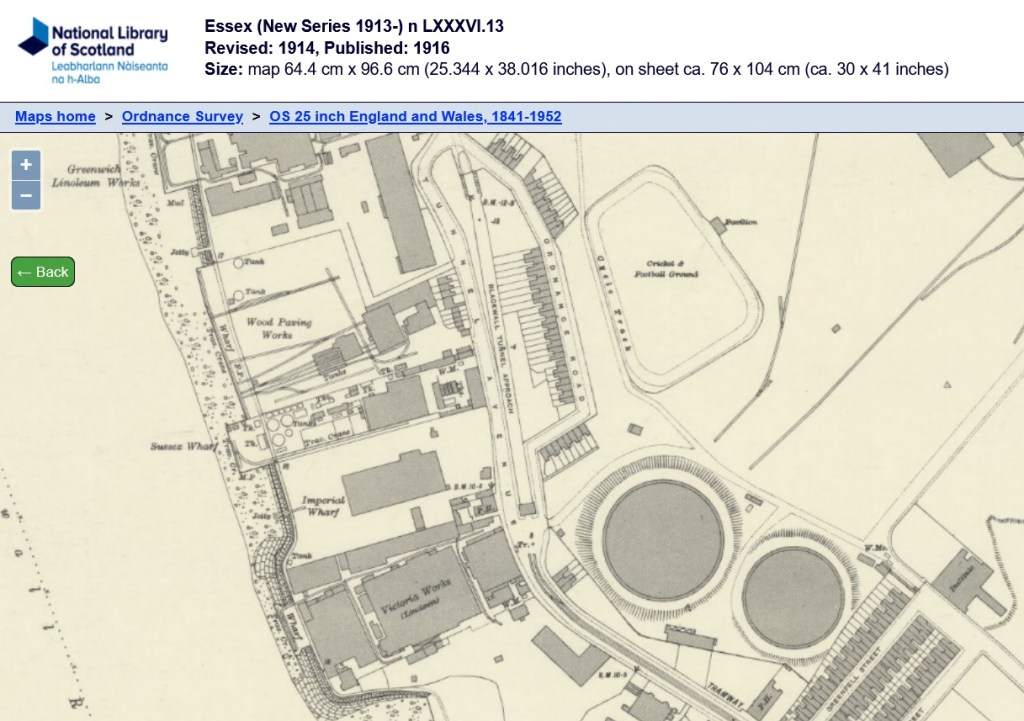

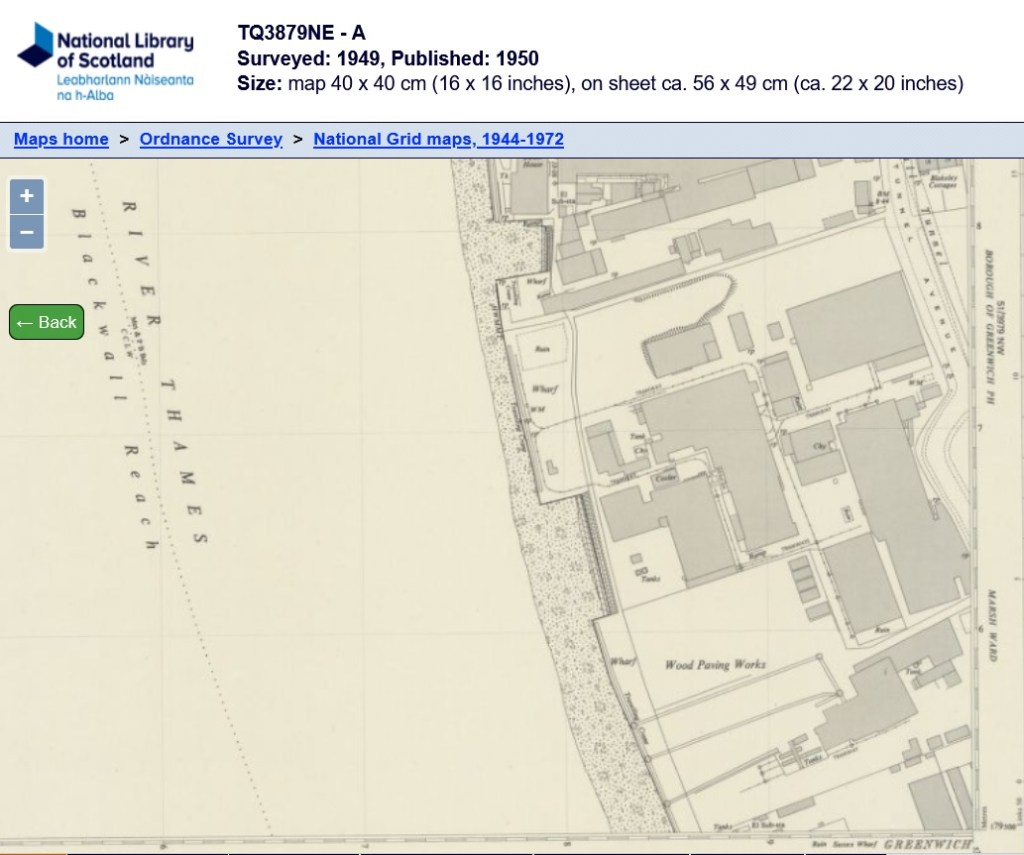

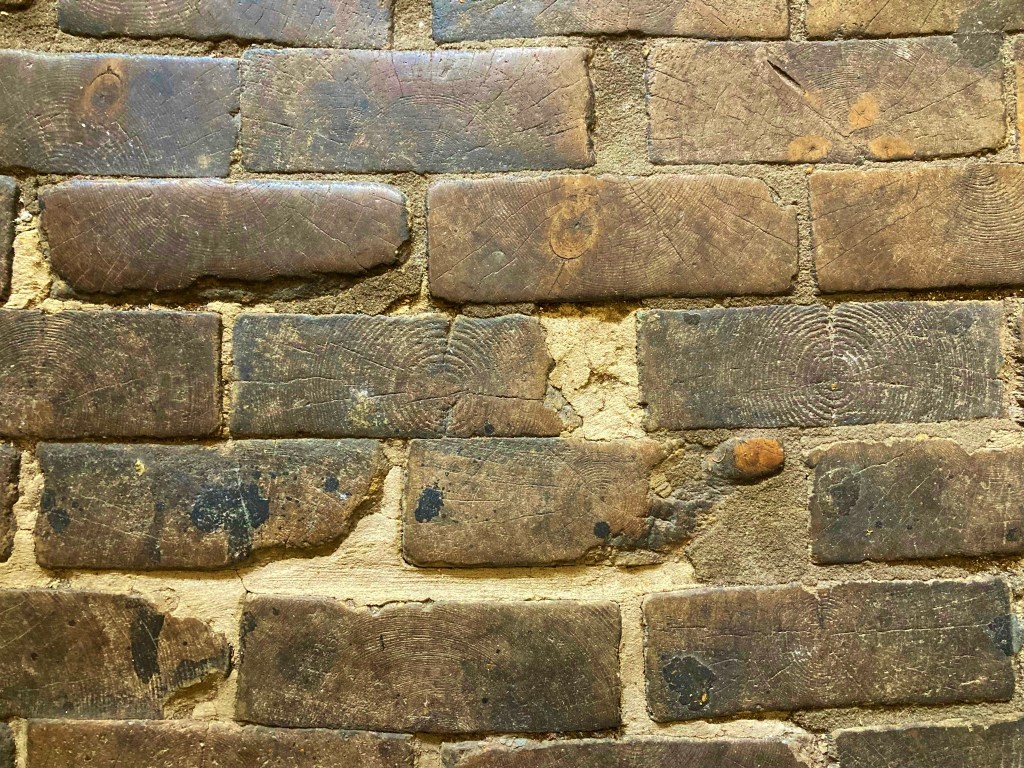

The Improved Wood Pavement Company were on Sussex Wharf at the western side of the top of the Greenwich Peninsula, by the Blackwall Tunnel Approach. No buildings remain but a fronting 19thC London Stock brick wall probably dates from that time. It developed from John Bethell’s wood preservation works. [2]

Edith Streets states “Bethell Chemical works. A wood preservative system was that pioneered in the 1830s by John Bethell. A barrister from Bristol. In 1848 he patented a way of ‘preserving animal and vegetable substances from decay’. The eventual success of Bethell’s process was to lead to the world wide use of wood for such things as railway sleepers and telegraph poles. At Greenwich the works eventually specialised in the manufacture of tar soaked wood block paving. … coal tar was purchased in bulk from the Imperial Gas Company works at St. Pancras and Haggerston. After Bethell’s death in the 1870s his wife Louisa retained ownership – and in the 1880s the works was transferred to the Improved Wood Pavement Company in which the Bethell family remained involved.

Improved Wood Paving. This company made tarred road blocks and built roads and pavements of them under contract to local authorities. It was on site in the early 20thC” [14]

John Mowlem ended up taking over the Improved Wood Pavement Company and their joint records are at the London Metropolitan Archive: “The Improved Wood Pavement Company Ltd was incorporated in 1872 to acquire the patent of improved Wood Pavement combining the use of wood with preserving composition packed with stone, and for laying and maintaining same. The Company took over the business and contracts of Samuel Norris and Benjamin Berkley Hotchkiss, who had already laid some wood pavements in London and elsewhere. Bartholomew Lane, EC2 had been paved in December 1871.

The original offices were at 32 Lombard Street, EC2, moving to Victoria Street, EC4, in 1876: in 1922 to Blackfriars House, New Bridge Street, EC4. By 1914 the Company was a contractor for wood paving, wood block flooring, sawing, excavating, concreting and had saw mills and works at East Greenwich.

Improved Wood Pavement Company Ltd became associated with John Mowlem and Co. Ltd, government and public works contractors of Westminster and formed with them in 1941 the Mowlem Paving Co. Ltd. During the 1950s the Company became a wholly owned subsidiary of Mowlems and in 1959 it ceased to operate independently. Its name was subsequently changed to Mowlem Construction (Plant Hire) Ltd and it is now a subsidiary of John Mowlem and Co. plc though Mowlem Construction Co. Ltd.” [15]

https://www.flickr.com/photos/friendlydragon/5919427663/

The novelist Walter Besant [16] described the East Greenwich works in 1898/9 in his posthumously published ‘London. South of the Thames’ “The pitch and tar works adjacent, with their open-air manufacture and pungent odours, are very noticeable, whilst next to these is the yard and works of the Improved Wood Paving Company, who import the wood, creosote it here in enormous cylinders, and prepare and lay it in the streets. Huge stacks of wood from foreign countries are here, seasoning and waiting their turn for the process. Alongside the wharf are barges full of new timber and others filled with old blocks, which have been sent to the yard to be trimmed up and relaid, on cheaper contracts, upside down.” [17]

( Walter Besant was brother-in-law to Annie Besant [18] the pioneering trade union and socialist activist who played a key role in supporting the Bryant & May ‘matchgirls’ and women strikers. [19] )

Sites in London

Which brings us to the here and now. Though probably the majority of the wooden paving was removed since the 1930s, famously Alan Sugar made his first break selling split blocks as fire starters from Clapton in the 1950s, there may well still be 100s of 1000s of blocks under tarmac waiting to be discovered and there remain a number of areas where wooden block paving is clearly visible e.g. at Pentonville Road and Chequer St, both in Islington and at Belvedere Rd by the old London County Hall, while wooden insets on old amenity access covers can often be see, but the vast majority of paving will be underground, under layers of tarmac, waiting to be discovered. A patch was uncovered at Dufferin St, the next street from Chequer St, probably coincidently, in 2020 for example but with the pipe works done was re-covered immediately.

Please do comment below if you have seen any in other areas of London and like the post if you like it!

Pentonville Road – maybe pre-WW2?!

Belvedere Road – post WW2?

Chequer Street – maybe more recent?

19thC sewer cover at Lauriston Rd, Hackney

At Brooke Road, Stoke Newington.

Visiting

All the sites mentioned are publicly accessible, but the un-covered road work blocks, and access covers are often ephemeral and covered in tarmac as soon as they are uncovered.

The site of the Improved Wooden Pavement Co can be seen on Tunnel Avenue, though there is nothing to see but the golf driving range that now occupies the site and maybe the old front wall.

The local pub, The Star in the East, now an electrical trades shop, which would have slaked the thirst of many a wood block maker for many decades, surprisingly still stands in an area in which almost everything is new, as does the beautiful gate house of the Blackwall Tunnel. [20]

And a short train ride to Romford, almost London, and you can can see an amazing wooden block paved side passage at the 17th-19thC Red Lion Inn, presumably laid in the 19thC. [21]

References

[1] https://www.ianvisits.co.uk/blog/2015/01/10/the-time-when-londons-streets-were-paved-with-wood/

[2] https://greenwichpeninsulahistory.wordpress.com/greenwich-marsh-by-mary-mills/chapter-17-coal-and-chemicals/

[3] https://issuu.com/southwark.news/docs/glw188

[4] https://roadswerenotbuiltforcars.com/wood/

[5] http://www.glias.org.uk/journals/9-a.pdf

[6] http://www.endgrain.org.uk/history/

[7] https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/2009/aug/londons-earliest-timber-structure-found-during-belmarsh-prison-dig

[8] Minutes of Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers Volume 78 1884 https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/Minutes_of_Proceedings_of_the_Institutio/tHXHAAAAMAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1

[9] The Surveyor and Municipal, and County Engineer, January 1913 https://archive.org/stream/surveyormunicipa44lond/surveyormunicipa44lond_djvu.txt

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eucalyptus_marginata

[11] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eucalyptus_diversicolor

[12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jarrah_Forest

[13] https://www.gripdeck.co.uk/about/our-story/

[14] https://edithsstreets.blogspot.com/2015/12/riverside-south-of-river-and-east-of_21.html

[15] https://search.lma.gov.uk/scripts/mwimain.dll/144/LMA_OPAC/web_detail/REFD+ACC~2F2809?SESSIONSEARCH

[16] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Besant

[17] ‘London. South of the Thames’ Walter Besant 1898/1912 https://www.charltonparks.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/London-by-Walter-Besant.doc

Also https://archive.org/details/londonsouthoftha00besa/page/n17/mode/2up

[18] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Annie_Besant

[19] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Matchgirls%27_strike

[20] https://pubshistory.com/KentPubs/Greenwich/StarEast.shtml

[21] https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1358531

Leave a reply to maryorelse Cancel reply