“… went to search for brick-earth” John Evelyn [1]

“… the Earth about London, rightly managed, will yield as good Brick as were the Roman Bricks, (which I have often found in the old Ruins of the City) & will endure, in our Air, beyond any Stone our Island affords” Christopher Wren [2]

Bizarrely, maybe, the Building London Blog has only had 1 post on brick. [https://buildinglondon.blog/2021/08/23/13-16thc-bricks-in-hackney-the-arcadia-beyond-moorfields/] Bizarre, as London is basically a brick city. Sure the ancient buildings were of limestone from Caen, Ragstone from Kent or Reigate Stone from Surrey, the grand, post Great Fire buildings are of Portland Stone and the Victorian embankments and bridges are made from granite, but the vast majority of London’s historic buildings are of brick. And not just any old brick but the local(ish) London Stock Brick, a mixture of brickearth, chalk and ‘spanish’ or old ashes. But it’s not as simple as it first appears!

London had no ready building stone to use, unlike cities like Bath, Oxford or Bradford, let alone the Scottish cities of Aberdeen, Glasgow and Edinburgh, but it does have a rock or substrate that can be used for building, after baking, and that is ‘brickearth’ [3] an Ice Age windblown silty sediment technically called Loess or in Britain, Langley Silt. [4]

And hundreds of thousands of London houses were built then from the brickearth dug out from directly beneath where the houses were to be built, though later in the 19thC the London Stock Bricks, of the same basic materials, were made and imported from the neighbouring counties of Middlesex, Kent and Essex in their hundreds of millions.

But little did I know when I started this blog that the humble London Stock Brick is the subject of debate as to it’s origin, specifically as to whether it was made from ‘loess’, we’ll come onto that, or clay like the ubiquitous 20th brick made by e.g. the London Brick Company. [5]

London bricks: made from loess/brickearth or London Clay??

I was brought up in Bedford, Beds in the 6ts and 7ts. I remember to the south of the town the deep, vast Oxford Clay pits and their clattering conveyor belts, the dozens of massive brick chimneys reaching to the sky, and the acrid smell when the dirty yellow clouds of smoke blew north over the town. And I learnt, logically, that therefore brick was made, like pottery, from clay and so I have always assumed that all brick was made from clay. And indeed it is widely stated and thought that the London Stock Brick is made from the 50 million year old London Clay [6] [7] [Nb keep watching out for a post on London Brick! ]

But it turns out that this perceived wisdom, shared by many, is not true when it comes to London and the key protagonist in this issue has been Ian Smalley, a soil scientist at the University of Leicester. [8] [9]

Smalley states that the London Stock Brick [LSB] is not made from clay or specifically London Clay but brickearth, a Loess [10] silt based sediment found, or used to be found, in London and significantly around London, mixed with ashes, to help them burn, and chalk to provide the yellow colour. Loess is defined here as “.. as an accumulation of windblown silt… classified as sediment, soil or rock….Any yellowish, carbonate bearing, quartz rich, silt dominated substrate (minor contents of [fine]sand and clay … formed by aeolian deposition and aggregated by loessification during glacial times would be widely accepted as (typical) loess.” [11]

One of the first outings for this argument was in Ian Smalley’s paper in 1987 for the British Brick Society newsletter when he plotted early brick buildings with brickearth deposits. He stated “ ‘Brickearth’ is an ancient term and is still widely used. It is also the cause of much confusion and imprecision in the scientific study of the loess deposits and brickmaking materials in Britain.” and it continues to be!

Smalley continued “The loess in Europe made excellent bricks, since it contained the right proportions of silt and clay for it to be fired without any difficult mixing or pretreatment. Many large loess deposits in eastern Europe are still supplying satisfactory bricks today and many smaller deposits supplied the bricks for the great Victorian expansion of London.” He further notes that “The way in which confusion has arisen, and precision been lost, can be seen when the Tomkeieff [ an important geologist ] definition of brickearth is consulted: ‘Naturally occurring clays which are used in the manufacture of bricks …. British brickearths are found in the Oxford Clay, the lower Lias and in the Wealden clays of Sussex, etc.” [12]

( Though not concerning London specifically it’s worth noting that some like the Firmins disagreed with Smalley’s thesis re early brick buildings stating “… we stand by our previous assertion that most early medieval bricks ‘were made from fine grained sticky … muds and clays’, which were certainly not brickearths as Smalley defines the term. Admittedly, some of these sediments may incorporate some primary or secondarily deposited loess but not sufficient to be called loessic brickearth.” [13] )

Smalley has developed his argument re London brick in a number of articles on his website e.g. re the London sewer system – “Over 300 million bricks were used in the construction of the Bazalgette sewer system for London. During the construction period there was a huge demand for bricks (and bricklayers) and the prices rose considerably. The obvious source of bricks was the multitude of brickworks around London all producing the London Stock brick- the classic brick made from the local brickearth!” [14]

And “Large parts of London are made from loess. London grew in the 19th Century; thousands of houses were built with loess bricks- bricks made from the London Basin brickearth. London was well placed with respect to bricks; it could become the great brick-built city. The thousands of houses were all heated by open coal fires which produced vast amounts of ash and cinders- which was collected by ‘dust-men’ and concentrated into vast dust heaps. This could be sent by sailing barges to the downstream brickworks to be used in the making of the classic Thames ‘stock’ bricks.” [15]

And more recently in his ‘London Stock bricks from the Great Fire to the Great Exhibition’ April 2021 he states “Much of London was built with London Stock bricks, which were made from the brickearth which was widespread in the Thames basin. The brickearth was remarkable material, the western fringes of the great loess deposits which were spread over Europe in Pleistocene times. This English loess was slow to be appreciated because by the time that geology had assimilated the idea of loess, and decided what loess was, and accepted the idea that brickearth was loess, most of the English loess had been converted into bricks. By the time of the Great Exhibition in 1851 most of the good quality brickearth had disappeared and London had spread over the disused brickpits.” He finishes by reinforcing the brickearth thesis “We are trapped into an overgenerous use of the term ‘clay’… [ though noting that while Brickearth is mainly silt, clay plays a key role of bonding ] The quartz silt gives the brick its dimensional excellence and strength, the added spanish gives it firing efficiency and the clay mineral content provides the important bonding phase.” [16]

“Other characteristics of the London stock result from its method of manufacture, two stages being especially important. The first of these is the practice of mixing the clay with what has been variously known as Spanish, soil, town ash, or rough stuff – that is, London’s domestic rubbish, which contained a large amount of ash and cinders. The addition of this sifted ash provided a built-in fuel when the bricks were fired, thereby considerably reducing the cost of production. During firing, the particles of ash were consumed leaving characteristic pock-marks on the surfaces of the bricks.” [17]

Smalley is not the only let alone the first person though to identify the use of brickearth with the LSB though as here Alan Cox in 1997 (imo Cox then confuses the issue by also then calling the brickearth, clay, throughout the article ) states: “The London stock is a type of brick the manufacture of which is confined to London and south-eastern England (particularly Kent and Essex). It is made from superficial deposits of brickearth overlying the London Clay, which are easily worked and produce a durable, generally well-burnt brick. This durability actually increases, since the London stock brick has the fortuituous advantage of hardening with age and in reaction to the polluted London atmosphere.” But in another clear example of this confusion he uses brickearth and clay interchangeably “Clearly, deposits of clay in different localities varied to some extent, but as a working hypothesis we can accept John Middleton’s estimate in 1798 that one million bricks per acre could be made from every foot in depth of brickearth, and that the average depth of brickearth was about four feet.”

Cox also describes the classic mix for the LSB – brickearth, ashes, also called ‘spanish’, from the fireplaces of London which still having enough combustible material in them helped them bake, to which was added chalk to colour.

Peter Housnell in BBS also follows the loess/brickearth theory “As is well known the London area lacks good building stone but much of the flood plain of the River Thames is overlaid by a geological formation known generally as brickearth, and it is this material, rather than the intractable London clay, which provided the basis for the ubiquitous stock brick from which much of Georgian and Victorian London was built.” [18]

The brilliant [19] of the late, great teacher and human/ist geographer Jack Robinson also identified in the 1980s that brickearth was key to brick making in Stoke Newington

“Brickearth was laid down at about the same time as the Taplow terraces. It is rather like the Loess of the continent, a fine-grained, wind-blown dust. During the Ice Ages the North Sea and Northern Britain were frozen. The Continent was an area of permafrost which melted slightly in the summers. The Arctic was an area of high pressure and the Continent, of low pressure. This produced cyclonic winds, giving an almost permanent eastern wind over England. Each summer the top few centimetres of the permafrost of the Continent melted into a fine dust which was carried by the wind to be deposited in large areas of South Middlesex and South West Essex.

Brickearth was valuable for making bricks and tiles and for market gardening. As a result, some deposits of Brickearth have been completely worked out. Brickearth produced the fine red bricks for the Queen Anne houses built after the Great Fire in 1666. The bricks for the early houses in Stoke Newington Church Street were made from Brickearth, while the Yellow Stock bricks for the houses in Clissold Rd, were made in the Thames Valley and contain Chalk.”

However Robinson then states “Most Stoke Newington houses were built of bricks made from local London Clay.” which does not seem correct. [20]

As always it’s worth looking at the 19thC literature and Edward Dobson in his encyclopaedic ‘Rudimentary Treatise on the Manufacture of Bricks and Tiles containing an outline of the Principles of Brickmaking’ clearly states that London Clay is not used to make bricks in London “…The brickmakers in the vicinity of London at present derive their principal supplies of brick-earth from the alluvial deposits lying above the London clay, the blue clay not being used for brickmaking at the present day.” Though he does categorise the brickearth into 3 types, one of which he calls “a strong clay” along with “malm, an earth containing a considerable quantity of chalk in fine particles” and a sandy, gravelly “loam”. [21]

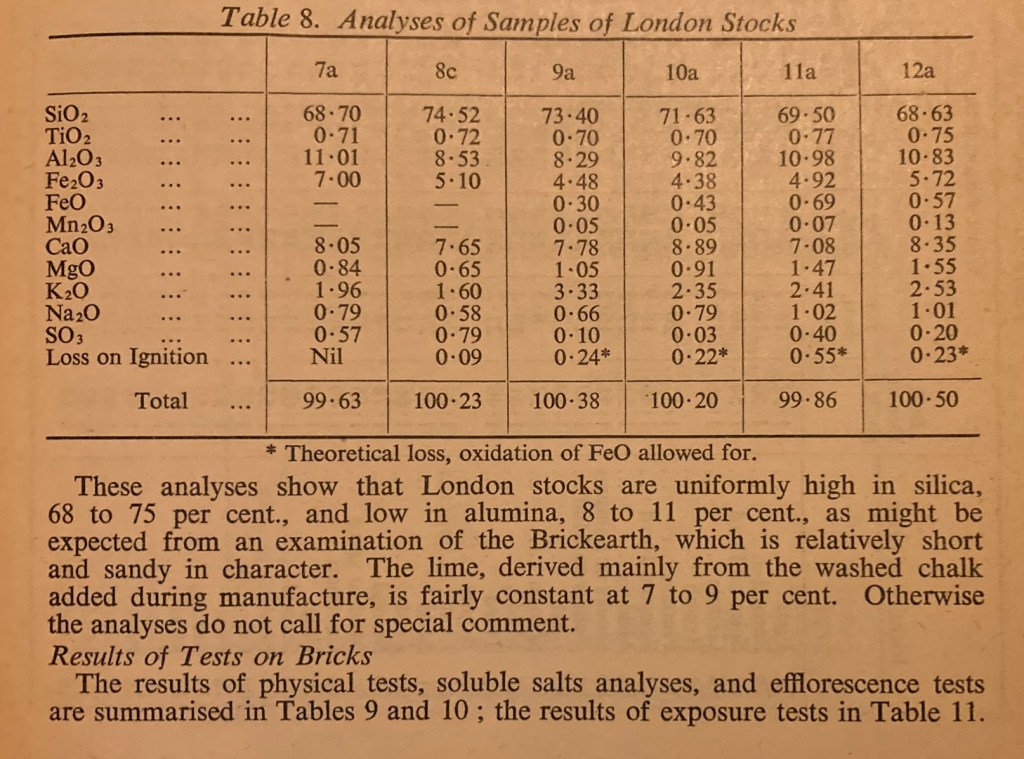

And the equally authoritative document on British bricks, ‘Clay building bricks of the United Kingdom’ by Bonnell, and Butterworth refers specifically to London stocks as “bricks made from Brickearth” and their analyses ( see pictures) show the higher levels of Silica, from silts, and lower levels of Alumina, from Clay, levels especially when compared to bricks made from e.g. the Oxford Clay. [22]

London Clay

However the London Clay theory remains widespread. Here is an example here from Andie Byrnes at the fascinating Russia Dock blog: “First of all, what is London stock? London stock, also known as yellow stock, is a type of brick. It is coloured pale brown to yellow made from a clay unique to the Thames basin area … To be termed London stock, the brick must be both manufactured from London clay and turn a shade of yellow when fired…It is made from a local clay called London clay, which is blue-black in its raw state, but weathers to a shade of brown and turns different colours when fired (i.e. when subjected to high heat to make it hard). The colouration is dependent on the clay used for making the bricks. The clay itself is a marine sediment and dates to the lowest level of the Eocene epoch, around 56-47.5 million years ago.” [23]

Or Joyce Dixon in the otherwise brilliant Londonist “ … the dense clay used for brickmaking. London clay …” [24] and the Highbury Wildlife Garden, [25] though Wikipedia which hedges it’s bets saying “brickearth or London clay subsoil which was then turned into bricks…” [6]

The otherwise fantastic Brickfield Newham seems to gets London Clay, clay and brickearth all confused and upside down “Let’s start with raw materials and the word ‘brickfield’. Is London clay a crop? The name makes it sound like clay can be harvested. To make a brick you need to mix raw materials to form brick earth. Brick earth is made up of true clay (alumina silicate) which gives plasticity. But clay would loose its shape during firing. So you have to add sand, aggregate or other chemicals to make it hold its shape and these can also change a brick’s appearance too. London clay deposits are from the Holocene period and are found in topsoil.” As we have seen above, brickearth is a thing in itself, not something formed buy us and it’s not made up of clay, that it has some that binds, though they are correct that the deposits, though brickearth not clay, are from the Holocene, the last Ice Age, not millions of years old like London Clay. [26]

The London Natural History Society, who should know/better, state “Impermeable London Clay is … a sea-bed sediment, laid down 56-34 million years ago in the Eocene epoch. It lies on top of the chalk, and in some places is 150m thick… and it makes very good bricks. … The classic yellow ‘London Stock’ brick is made from this clay, and can be seen in houses and buildings all over the capital.” [27]

Peter Ackroyd in his seminal ‘London: the biography’ states, though tbf he doesn’t clearly say London Clay “…the clay and the chalk and the brick-earth have for almost two thousand years been employed to construct the houses and public buildings of London. It is almost as if the city raised itself from its primeval origin, creating a human settlement from the senseless material of past time…This clay is burned and compressed into ‘London Stock’, the particular yellow-brown or red brick that has furnished the material of London housing.” Though then stating that “The houses of the seventeenth century are made out of dust [ loessic brickearth ] that drifted over the London region in a glacial era 25,000 years before.” suggests he thinks everything else is made from London clay. [28]

And this from the London Geodiversity Partnership who have done great work identifying sites of important geological interest in London is also then I believe incorrect as to past usage .. see Dobson above clearly saying London Clay was not generally used. “ The London Clay Formation does not meet modern standards for brick-making due to its high smectite [ clay essentially ] content, which causes extensive shrinkage and distortion during drying and firing. However, in the past it was used with the admixture of sand, or chalk, or in some instances blended with street sweepings of grit and cinder…The London Clay was used more for tiles and pipes.” [29]

To conclude I think Smalley is right and re-stating what Bonnell and Butterworth and Dobson previously that London Stock Bricks were not, at least generally made from London Clay but were made from brickearth, a silt with some clay, initially in London, but as the 19thC went on, increasingly at large brickfields outside of London in the west of Middlesex, in the south of Essex and the north of Kent.

Middlesex, Essex and Kent

After the (inner) London brickearth was worked out in the mid/late 19thC the brickmakers went out of London to Drayton in Middlesex, Sittingbourne and Faversham in Kent and various sites in Essex, which sat on brickearth, rather than use the ubiquitous London Clay, although a few brickworks seemed to have done e.g. Chingford. Indeed, if you think about it, if they had being using the London clay why would they have imported bricks from outside of London? With London Clay a 100m deep I think there would have been the development of an industry similar to that at Peterborough and Bedford with vast pits and soaring chimneys. But as Dobson noted, it was clearly just not that good for brick making.

Here Arthur Perceval illustrates the Faversham, north Kent brick industry connection with London and the use of chalk to give the bricks their canary yellow colour “The secret was not just in the brickearth, though this was of high enough quality. It was in the process. For facing bricks the fashion was for yellow; and someone had discovered a century earlier than if you mixed chalk, also readily available, with the brickearth, the end product came out yellow, instead of the natural red…Even more important, someone had discovered at about the same time that if you mixed coal-ash with the brickearth and chalk, you ended up with a brick which was self-firing. No need for kilns. … The ash still had enough energy left in it to burn, and bake the bricks. These were the famous ‘London’ stocks – in fact, mostly made in Faversham and the Sittingbourne area.” [30]

Benfleet in south Essex was another major London Stock Brick making area and again based on brickearth. This from Benfleet History initially imo gets brickearth and clay mixed up but later makes it clear – “Brick-clay has a higher clay content and is more suited to pottery and tile making, due to its greater elasticity. Brick-earth, on the other hand, has a much lower clay content and is predominantly quartz” [31]

This blog has posts in the pipeline on the Middlesex, north Kent and Essex brickfields and works. Keep watching this space!

Canary Yellow Clapton

When people think of bricks one of the other truisms is that bricks are almost by definition red – redbrick. And if you look at the 1000s of terraces of the industrial towns of the Midlands or North or even the oldest brick buildings in and around London like at Lincolns Inn and Hampton Court Palace, they are. But one of the defining features of the London Stock Brick, is that it is yellow and in it’s original colour a shocking canary yellow not dull as this states below! PICS And indeed when people in recent decades think of a LSB it is often the blackened surface after 100 years of pollution. It was only the gentrification and sandblasting of many Victorian terraces, e.g. in Clapton, in the last 2 decades that has exposed the original colours, though maybe after firing they always had some darkness.

“London Stocks have a dull brownish yellow colour which can be surprisingly attractive in mass brickwork; they are also good quality products. Their origin seems to lie in a change in architectural taste in the early eighteenth century, when something closer to the colour of stone was desired in place of red brick. It was discovered that by mixing chalk, in the form of a slurry, with the basic raw material an appropriately fulvous hue could be achieved. The raw material was brickearth above the London Clay of London, Middlesex, and the Lower Thames Valley…further mixed with ash and cinder (known initially as ‘Spanish’, later as ‘roughstuff’) from domestic fires in the metropolis.” [32]

The yellow was apparently just fashion, though not everyone agreed: Cox quotes “… in 1756 Isaac Ware stated very firmly that: ‘the grey stocks are to be judged best coloured when they have least of the yellow cast; for the nearer they come to the colour of stone . . . the better’” and so brickearth with raised levels of chalk, Malm or Marl, was favoured but “..in 1797 John Lee took out a patent for ‘A Certain Mixture of Chalk, Whiting, or Lime, Together With Clay, Loam, or Earth, For Colouring and Making Bricks’,” and thereafter malm bricks began to be manufactured artificially, chalk being mixed with inferior clays and earths. By the mid-nineteenth century almost all malms were made using an elaborate artificial process.” [17]

Smalley also notes in this article on Kings Cross Station how the yellowness of the LSB was created by adding Chalk, c10%. [33] [34]

p.s. why are they called ‘stock’ bricks? Because they were made in molds on ‘stock boards’? Or as they were just what all brick sellers had!

Maybe both” 😀

“The term ‘stock brick’ can either indicate the common type of brick stocked in a locality, or a handmade brick made using a stock.” [6]

What to see

Actually unlike other posts, this post has not much in particular to see in the sense there are no scenic brickearth pits I can point people in the direction of, so the best thing is though to simply look at the 100s of 1000s of houses in London that were raised in the 19thC from the brickearth beneath them and in particular look out for where they have been sand blasted recently and see the amazing canary yellow colours that appear! Also note the pock marks where bits of organic matter burnt away, the dark bits of charcoal and the pebbles of all shapes and colours that made it through the sieving!

References

[1 http://britishbricksoc.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/BBS_103_2007_April.pdf

[2] from the Life and works of Sir Christopher Wren. From the Parentalia; or Memoirs by his son Christopher. 1750 https://archive.org/stream/lifeworksofsirch00wren/lifeworksofsirch00wren_djvu.txt

[3 ]https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brickearth

[4] https://data.bgs.ac.uk/id/Lexicon/NamedRockUnit/LASI

[5] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Brick_Company

[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_stock_brick

[7] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/London_Clay

[8] http://loessground.blogspot.com/

[9] https://www.blogger.com/profile/10715518067515369104

[10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loess

[11] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1040618215002190#

[12] The nature of ‘brickearth’ and the location of early brick buildings in Britain – lan Smalley http://britishbricksoc.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/BBS_41_1987_February.pdf

[13] http://britishbricksoc.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/BBS_47_1989_February.pdf

[14] http://loessground.blogspot.com/2020/10/london-stock-bricks-in-bazalgette.html

[15] https://loessground.blogspot.com/2020/08/making-bricks-from-loess.html

[16] ‘London Stock bricks from the Great Fire to the Great Exhibition April 2021’ https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350689973_London_Stock_bricks_from_Great_Fire_to_Great_Exhibition

[17] A Vital Component: Stock Bricks in Georgian London Construction History Vol. 13. 1997 https://www.arct.cam.ac.uk/system/files/documents/chs-vol.13-pp.57-to-66.pdf

[18] http://britishbricksoc.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/BBS_93_2004_Feb_.pdf

[19] https://www.locallocalhistory.co.uk/

[20] https://www.locallocalhistory.co.uk/geology2/index-m.htm

[21] ‘Rudimentary Treatise on the Manufacture of Bricks and Tiles’containing an outline of the Principles of Brickmaking’ 10th Edition 1899 https://www.google.co.uk/books/edition/A_Rudimentary_Treatise_on_the_Manufactur/0RYLAAAAIAAJ

[22] ‘Clay building bricks of the United Kingdom’ by Bonnell and Butterworth. National Brick Advisory Council, Paper 5, 1950; London: H.M.S.O.

[23] http://russiadock.blogspot.com/2013/10/the-wonderful-world-of-london-stock-and.html

[24] https://londonist.com/2013/11/the-secret-history-of-the-london-brick

[25] http://highburywildlifegarden.org.uk/victorian-highbury-bricks-brickfields/

[26] https://www.newhamheritagemonth.org/records/brickfield-newham/

[27] https://www.lnhs.org.uk/index.php/articles-british/249-geology-of-london

[28] https://www.theguardian.com/books/2001/aug/29/firstchapters.highereducation

[29] http://londongeopartnership.org.uk/wp/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Londons-Foundations-2009.pdf

[30] http://britishbricksoc.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/BBS_109_2009_Mar_.pdf

[31] https://www.benfleethistory.org.uk/content/browse-articles/buildings_and_development/brickworks/the_process_of_brick_making

[32] Westminster Cathedral: its Bricks and Brickwork by Terence Paul Smithhttp://britishbricksoc.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/BBS_110_2009_Jul_.pdf

[33] ‘London Stock Bricks: development of strength and yellow colour in bricks from the loess of South-East England’ Ian Smalley April 2021 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/361412794_Why_is_Kings_cross_yellow_The_triumph_of_the_everlasting_brick

[34] https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353346944_London_Stocks

Leave a comment